The Public Trust would work with local authorities, funders, operators, and communities to acquire buildings, place them in asset-locked structures, and ensure they are permanently used for community purposes.

The white paper addresses three key questions:

Could we establish an organisation, based on the principles of the National Trust to provide stewardship for our civic and community infrastructure?

How can we ensure that social and community infrastructure focuses on the needs of people today - affordable childcare, preventative health, workspace and studios, cultural production and performance, libraries, active wellbeing centres, green economy, experimental uses and independent retail?

What stops us from seeing this as critical infrastructure and why can we not create a solution at scale?

Introduction

Across the UK, community and civic buildings are disappearing. Rising property values, constrained council finances, and reliance on development-led delivery mean that spaces for local enterprise, childcare, health prevention, learning, and culture are increasingly fragile, temporary, or unaffordable. Although widely recognised as valuable, community infrastructure is not treated as critical national infrastructure.

This white paper proposes a new solution: The Public Trust. A national organisation dedicated to protecting, owning, and stewarding community buildings for public benefit. It will introduce three core innovations:

National-scale stewardship of community assets

Multi-stakeholder ownership

Conversion of social impact into equity

White Paper Authors

Harry Owen-Jones is co-founder of 3Space, a charity providing community spaces across the UK. He has led affordable workspace and community infrastructure projects from strategy and policy work through to mobilisation and operation.

Chris Paddock has over 20 years’ experience in economic development, placemaking and public policy, most recently as Policy and Strategy Director at London Councils, leading London’s collective response to English Devolution and work on new systems and governance.

1. The Public Trust - protecting the here and now

Preserving historic places, natural landscapes, and our cultural heritage, the National Trust is universally recognised as a force for good. Balancing preservation with accessibility, it ensures the beauty, history, and culture of the UK remain protected for future generations to enjoy. It is one of our great institutions, with a net asset value of £1.7 billion and an annual income of £766.2 million.

We are among the 5.35 million National Trust members, an extraordinary number. We are strong advocates for the National Trust and don’t resent the cost of our memberships, but have recently come to reflect on the different types of value we attribute to buildings, through our work with 3Space and government partners delivering community buildings. As a society what do we value more - our past or our present?

And what would a 21st century model look like for such an organisation? Maybe less Victorian philanthropy, more local co-ownership. This organisation could be called The Public Trust. If the National Trust protects historic buildings for the nation, The Public Trust can safeguard important buildings for the public that are still teeming with community and purpose.

Sizergh Castle, a National Trust property in Cumbria

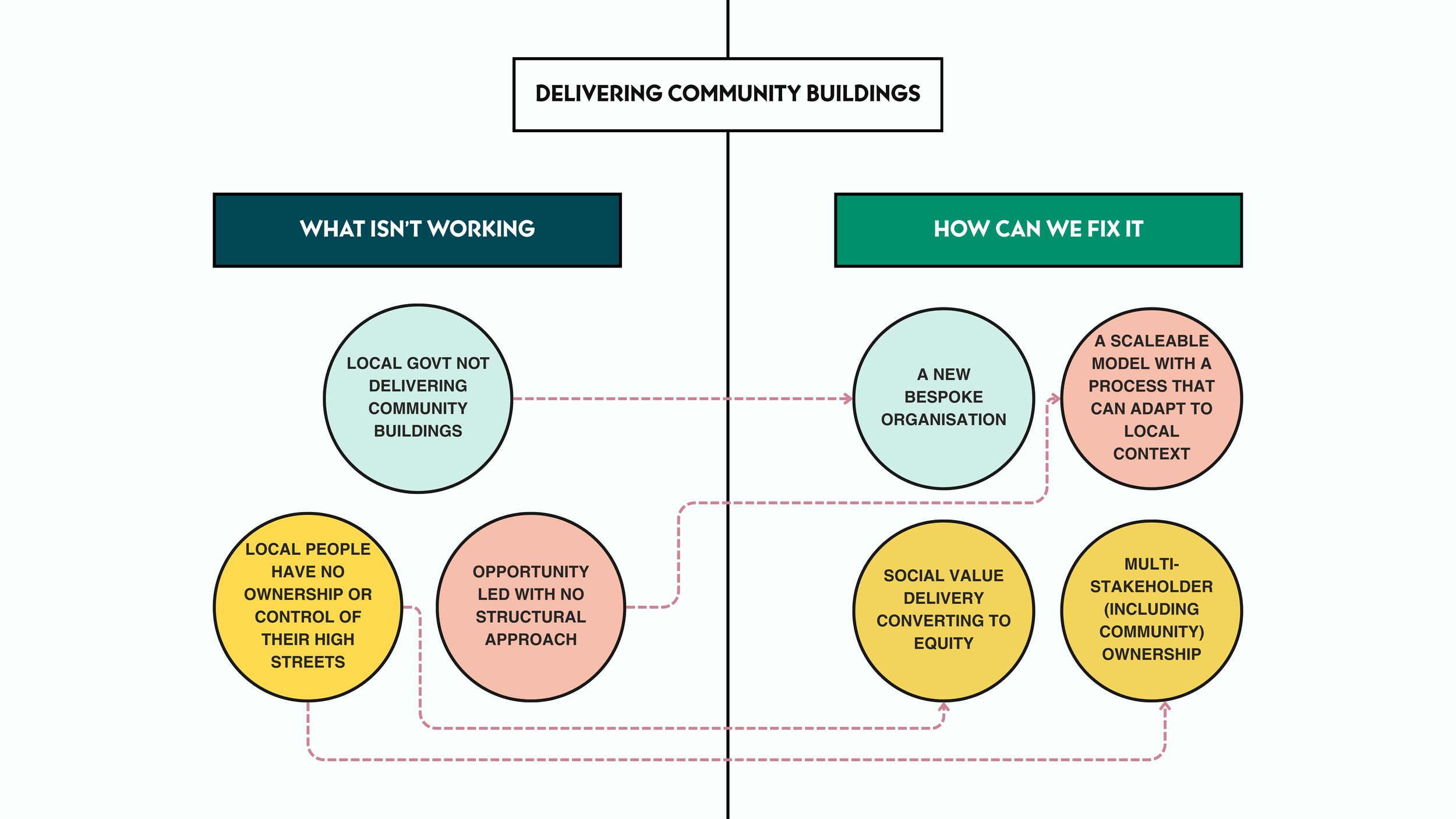

2. How do we deliver social infrastructure at the moment

Beyond the direct delivery of services, local government is expected to use a proportion of their property assets to foster social value generating and foundational economy uses. Public buildings are owned by the public - government is the organisation put in place to manage them. However, the best value duty of councils can restrict how they are used.

This tied to 15 years of cuts to council funding and rising demand for statutory services like social care and homelessness support makes it increasingly difficult for Councils to justify using the buildings they own for anything other than revenue generation or core service delivery. Many councils are under pressure to sell assets to fund services and plug budget shortfalls further reducing the opportunity. Without subsidised rents in public sector owned properties there is a risk that the types of use mentioned above will be displaced from UK high streets and local centres.

NISTA (The National Infrastructure Service and Transformation Authority) and government’s 10 Year Infrastructure Strategy, recognise the value of social infrastructure but limit this only to the health, education and justice estates. Plans identify the need to provide much needed maintenance to publicly owned assets, but provide nothing on the wider potential to create community facilities which directly enable people to live healthier and happier lives.

Currently, social infrastructure is undervalued, not seen as critical and crowded out by other important investments. We need a new national approach which elevates community facilities, celebrates their value and recognises the nuance in their delivery. This is the point of the Public Trust.

3. Why we need change

3Space operates buildings that deliver public goods. Since 2010 the charity has overseen some great projects but they are time limited and opportunity led - 46 buildings across the UK have provided space for artists studios, makerspaces, an agri-tech incubator, start-ups, refugee support, combatting food poverty, and sustainability initiatives.

3Space are one of a group of operators who exist because they believe some buildings should support communities, not profits. Ultimately, in most cases organisations like 3Space don’t own the buildings and at some point they are redeveloped or go on to serve other functions. It’s piecemeal, hand to mouth work which makes long term planning difficult for both operators and tenants.

The sad truth is that local government is just not able to allocate the assets and resources to realise this. We end up looking at developers to fill this gap. The planning obligations (CIL, S106) created to do this, produce inequality and inconsistency at a national level, with those places with the scale and capacity to deliver development benefitting disproportionately. These funds are (as we are currently seeing in London) also increasingly fodder to tackle deficits in viability in development, meaning delivery of good community infrastructure becomes further tied to a private market which is struggling to lever investment.

3Space’s International House is the first Living Wage Building in the UK housing a blend of startups, non-profits, sustainability initiatives and cultural production.

Green Lab was the 1st UK agri-tech incubator in the UK, housed within a 3Space and project built entirely from reclaimed and salvaged materials.

This is not just about public finances. There is a political and democratic imperative to deliver better community infrastructure. Enshrined with the English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill is a commitment to community ownership and organisation. The 10 Year Health Plan commits to prevention and neighbourhood health, whilst Public Service reform is underpinned by the principles of ‘strengthening localities’ and ‘building for scale’. Universal access to spaces protected in perpetuity should be seen as a vital facilitator of this.

It might be time to accept that the current system simply cannot deliver the community assets which residents desire or even expect, and do not provide the safe and strong foundations we need for policy change. It may also be the time to challenge the assumption that councils are the best organisations to look after local assets on behalf of their constituents and that a more structured approach, at scale, creating a new approach to ownership is the way to go.

4. A new national model of community ownership

The Public Trust could work nationally with funders and local government to secure and deliver spaces in perpetuity, not just for local communities but with them, providing local stakeholders with ownership and control of buildings. With this comes control of the outcomes they can support.

Currently, similar models of community ownership and stewardship tend to happen at the margins when all market solutions have been exhausted. More often than not, this requires the will and resources of individuals and groups and their preparedness to undertake this work for little or no financial reward. This means projects have an inherent delicacy, often reliant on too few points of success or failure. The Public Trust seeks to create scale and critical mass which recognises the role community infrastructure plays in the national public good.

Unlike the National Trust which holds the assets in perpetuity, the Public Trust can play a transitional role in the ownership of their buildings. Over time it would divest the ownership of buildings into the hands of local people in return for rent, positive place based outcomes like job creation, support for local young people, public health benefits, or for playing a hands-on role in managing the space.

The ownership of the building will be asset locked and the Public Trust can provide a supporting role through asset management functions and project administration.

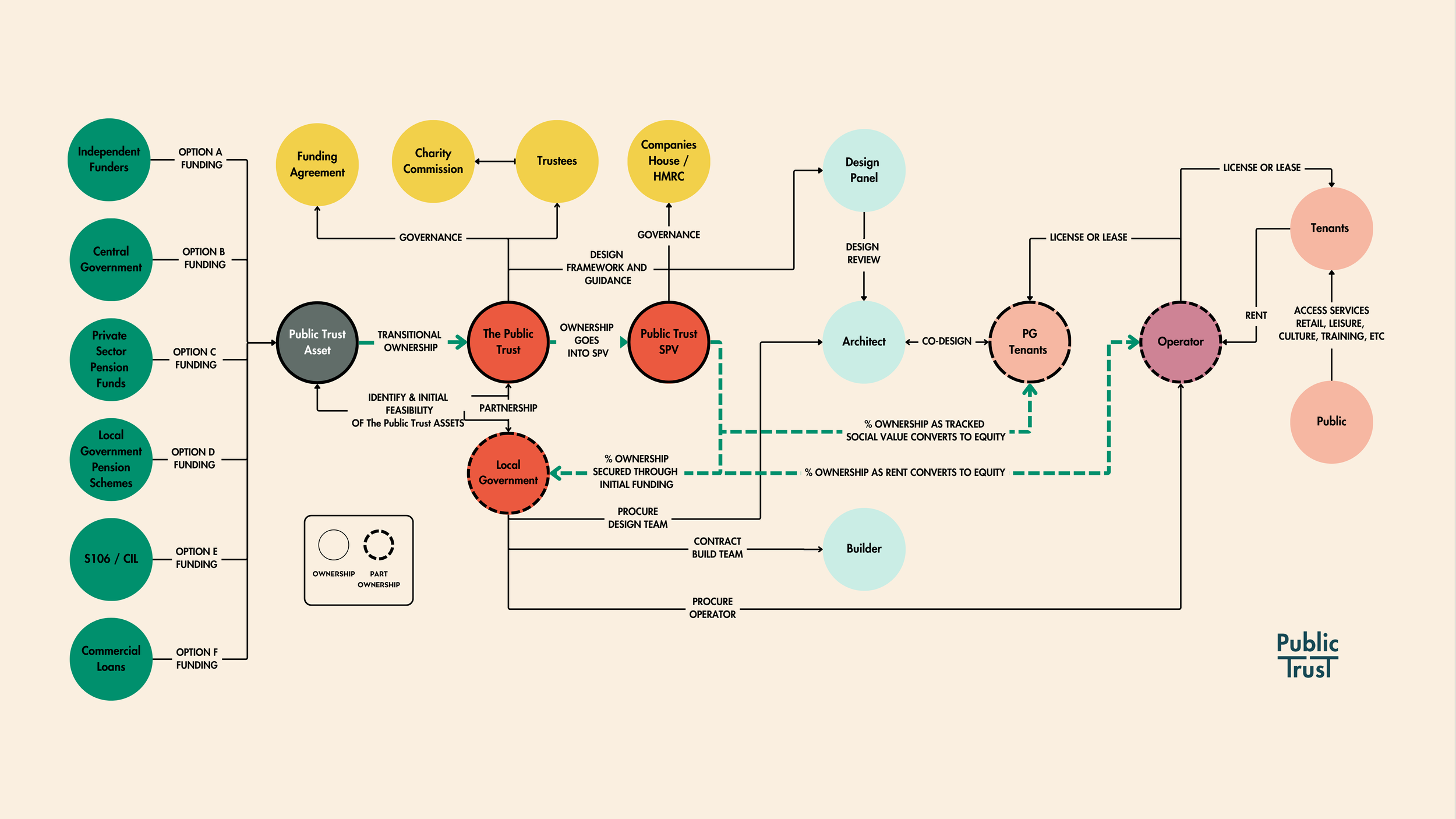

The Public Trust ecosystem, showing a proposed model for funding, governance, ownership and delivery

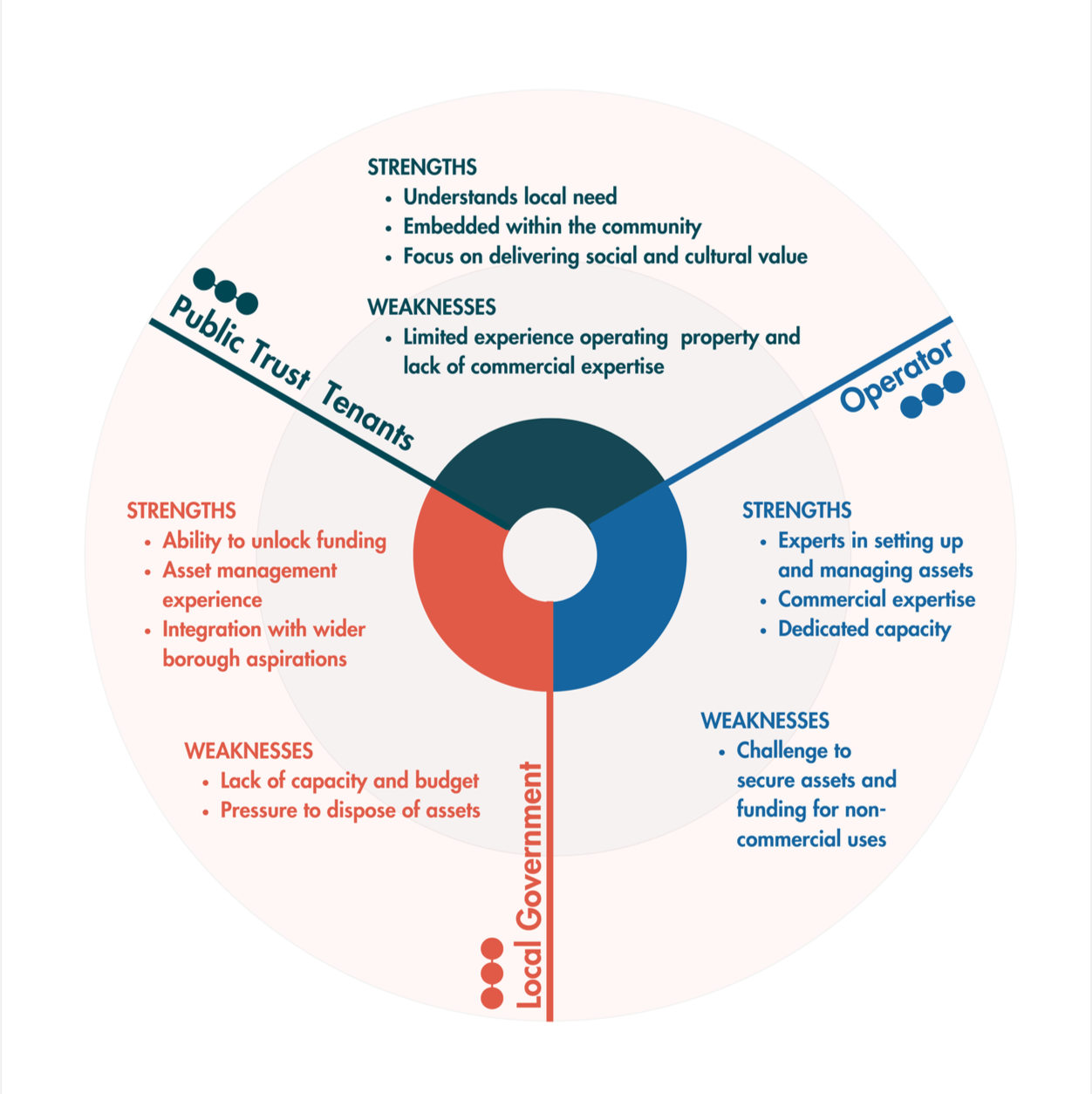

5. Why multi-stakeholder ownership

Multi-stakeholder ownership can combine the strengths and mitigate the weaknesses of public, private and community organisations

Councils are well placed to understand local social and economic needs and they remain an important partner, but given the pressure on local government finance, they may not be the most effective day to day leads on asset management. We need a different pathway to finance and own buildings. Multi-stakeholder ownership can offer an alternative model of public ownership.

The partnership model we are proposing blends the local expertise of councils, the hands on skill-set of operators and the social value delivery of Public Trust tenants. It empowers communities in the spirit of the government's Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill, whilst blurring the boundaries (and hierarchies) between public, private, community and philanthropic partners.

The Public Trust facilitates each partner to own a share in every project. We believe this will provide each project with a broad skill-set that balances community needs with commercial sustainability. Working at scale allows local nuance and responsiveness whilst mitigating the risk which is consistently sinking great projects around the country.

6. Converting impact into ownership

Whilst social value creation can unlock funding or support the case for a below market rent, it often goes without reward.

The built environment sector loves to put a £ figure against social value delivered. There are numerous social value toolkits and methodologies with a whole industry built up around it. This can be necessary to feed into a business case or justify decision making but social value outputs tend not to be given the same weight as other economic or commercial outcomes, which can render them meaningless.

Part of the frustration is that ‘social value’ is nebulous and for the community organisations who produce it they often have nothing concrete to show for it. The Public Trust can change this. Funders can and should be supported to invest in social and economic outcomes with clear and consistent understanding of their value to society. This is a critical principle of the Public Trust, recognising the inherent public goods realised in community infrastructure and converting this into equity, rather than just noting it in a social value report.

If funders were to provide the Public Trust with the capital to buy a building, that could be converted into an SPV or CIC with ownership and equity divested over time to Public Trust tenants for social impact and local outcomes they generate. This removes both uncertainty and overheads allowing Public Trust tenants to focus on their work and community impact. The buildings would be asset locked, providing space for local communities in perpetuity.

7. Recognising the power of the collective

Both the Arts and Heritage sectors have recognised the power in a collective approach. Be that the relatively young Creative Land Trust in London or nationwide titans such as The National Trust or English Heritage. There isn’t an equivalent for community buildings. Recognising the need for a counterpart to advocate for and organise how community buildings are safeguarded, managed, funded and owned is a surprising omission from our national landscape which needs a big solution. We propose that the Public Trust should fill that void.

8. Getting started

The Public Trust offers an optimistic, practical response to a system that no longer serves communities as it should. By treating community infrastructure as critical national assets, it reframes these important spaces not as a liability, but an investment in the nation's creativity, enterprise, health and social cohesion.

Working at scale, but rooted locally, it can unlock new forms of ownership, reward social impact, and give communities genuine control over the spaces they rely on. Just as the National Trust safeguards our past, the Public Trust can confidently make our lives and society better today.

This cannot be achieved through a series of local pilots. It requires commitment, a critical mass of resource and political will. It needs national coverage and the creation of a ‘national commons’. It must resonate in all places, from the busy high streets of London to the underserved rural villages of Cumbria. It also depends on government (and HM Treasury in particular) recognising the value of community facilities. It will need the transfer of assets from the public and private sectors and incentivisation of philanthropic investment.

This paper is intended to start a conversation, generate new ideas and build a coalition.

Additional information

Who we are:

The Public Trust is being developed by the co-founders of 3Space Harry Owen-Jones and Andrew Cribb. They have delivered 46 community buildings across the UK since 2010 working with public, private and third sector partners. The project 3Space is best known for is International House in Brixton that employs a cross-subsidy model to house community and cultural uses alongside more commercial tenants.

Contact us:

Email: harry@3space.org

Website: thepublictrust.org.uk